Why History Matters: A Teacher’s Rationale

When I was working on my undergraduate degree in the early 1980’s, a boyfriend questioned my choice of major. “Why does history matter anyway? What’s a history degree going to get you besides winning at Trivial Pursuit?”

Although I relished beating this guy every time we played the board game, my pursuit of the past had loftier aims. For 26 years I taught history to high school students. Now I write history books for children and teens. You see, I knew all along what my boyfriend didn’t. Understanding history isn’t trivial. It’s vital.

Why is History a Required Class?

In my early years of teaching, I wasn’t a very effective or engaging teacher. I lectured a lot and assigned textbook chapters and assessed my students’ memorization skills on multiple-choice tests. Because history fascinated me, I assumed everyone would find the subject interesting, regardless of how I taught it.

The kids would whine, “Why do we have to learn all this stuff?”

I’d stare at them. “Because history is so cool.”

Twenty-eight pairs of eyeballs would roll.

“Because it’s important!” I’d try again.

Twenty-eight blank faces would wait for me to explain why. Although I instinctively knew history mattered, I couldn’t articulate the reasons.

“Because it’s going to be on the test!” My final retort always ended the conversation.

This was no way to win history converts.

Fortunately, some invaluable teacher mentors and grad school professors pushed me to rethink my pedagogy. I learned how to craft interesting and relevant lessons. Then I developed a strong rationale for why studying the past is important, and on the first day of every new school year, I presented this “sales pitch” to my classes.

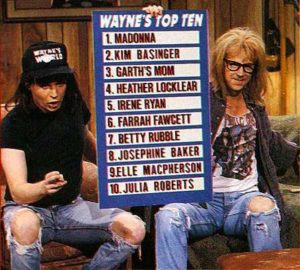

Top Ten List: Why History Matters

- Understanding the past helps us understand the present.

- History helps us understand human nature and, thus, ourselves.

- Exploring history requires us to view events through different cultural lenses, a skill that can help us understand diverse people in the modern world.

- History broadens our perspective and gives us the long view of civilization’s evolution.

- Understanding history provides inspiration.

- History provides us with an identity.

- History contributes to our moral understanding and fosters empathy.

- History teaches us the consequences of choices.

- The disciplined study of history builds critical thinking skills, essential for citizens in a democratic society.

- Exploring history is exciting and fun.

Be History’s Cheerleader

If you develop a Top Ten List or a similar rationale, you will demonstrate to students your belief history matters. A teacher’s convictions are important. If it appears that you’re just putting time in to collect a paycheck, how can you expect students to challenge themselves and do their best work? You need to be history’s cheerleader.

Prominent historians can help you explain the importance of history.

David McCullough, author of many acclaimed works including John Adams, argues that history shows us how to be human. “It’s a marvelous antidote to the hubris of the present.” Check out this short interview on YouTube where David McCullough answers the question “Why is history important?”

Presidential historian Doris Kearns-Goodwin believes history helps us see things from other people’s perspective. “When you have lack of empathy, when you have lack of sides seeing each other, something goes wrong in a country.”

In a 2010 interview, Nell Irvin Painter, acclaimed scholar of African American history, insisted that well written history allows us to see people as individuals so that we think about them beyond their race, class, or gender “…so that one woman is not interchangeable with another woman, and one black person is not interchangeable with another black person.”

Think like a Historian

The way history is packaged and taught in elementary and secondary schools devalues it. Textbook companies present the past as a single narrative, a collective memory that can be distilled into several hundred pages. Many history teachers (including me when I was a novice) emphasize the memorization of this narrative. This story then becomes a national myth. But that’s not history.

The past is not a single narrative, but rather a mess of chaotic memories often in conflict with each other. Historical interpretations vary depending on the sources a historian uses and his or her ideological bent. Historians debate their conclusions, often vigorously. When new sources are discovered, long-standing conclusions must be reconfigured.

An author in the Atlantic, in The Problem with History Classes, describes history not as a myth to memorize but as a wrestling match. Why not teach history that way? What student wouldn’t rather spend the class wrestling instead of reading a textbook?

But it takes skills to be a good wrestler, and the same is true to be a good historian. Kids need to be taught how to interpret the past if they’re going to understand why history matters.

Enter the History Teacher

To help students develop historical thinking skills, teachers must “do history” rather than just teach it.

The Greek word for history is ἱστορίa, “learning or knowing by inquiry.” History defined this way means the student is actively involved in interpreting the past. For teachers who love to tell a great story, reframing your role will be challenging. But once your students begin to “do history,” you’ll never go back to teaching the past as a single static narrative. That process just won’t feel right.

For students to “do history,” effectively, they need key tools. I call these the Time Traveler’s Tool Box.

These tools are the critical thinking skills students need in order to formulate strong historical interpretations.

Historical Thinking Skills

Questioning: Historical inquiry begins with asking what do you want or need to know. The right questions can launch you back in time.

Interrogate Sources: Identify the author, date, and purpose of a document and evaluate the author’s claims and supporting evidence. A fun way to introduce this process is by giving students documents from your own life to dissect.

Corroboration: Evaluate multiple sources and identify and reconcile the disparities and biases in these sources. The Stanford History Education Group introduces the skill of corroboration in a way kids can relate to with a lesson called Who Started the Lunchroom Fight.

Contextualization: Interpret an event, or document, or action in relation to what else was happening at the same time and in the same place. History doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Here is where your lectures, documentaries, role plays, and well-written secondary sources are helpful.

Claim-Evidence Connection: Craft a plausible argument based on an evaluation of multiple sources and reference evidence from these sources as support for this position.

Why It’s Worth It

Engaging students in active historical inquiry isn’t easy. Kids grasp concepts and skills at different paces, and teachers must individualize their instruction to meet the learners where they are. Teaching students to do history is often exhausting.

But as each school year draws to a close, most of your students will understand the elements of a well-written thesis. They will have evaluated and interpreted primary and secondary sources. They will have synthesized their findings into a coherent whole, some more coherent than others, but remember these skills take years to develop. The kids will have grappled with cause and effect and identified patterns of change and continuity. By exploring history through the eyes of diverse people, students will have developed a deeper understanding of contemporary society. You can end the school year with this confidence: Long after your students have forgotten the dates and names of people and events from the past, they will still carry critical thinking skills and historical insights into the future.

Trivial? Definitely not.

History matters.

What strategies do you use to persuade your students that history is important?

Great way to think about teaching and learning history; wish some of my teachers had said more than just “because it will be on the test!”

Thanks, Suzie. I’ll admit there were plenty of times I did say “because it will be on the test.” 🙂