The Elucidating Grannies Follow Whispering Bones to Historic Jamestown

The Elucidating Grannies chose Jamestown as the first stop on our exploration of colonial life in Williamsburg, Virginia. The whisper of a young girl’s bones lured us there. For background on the origins of the Elucidating Grannies, see my previous post.

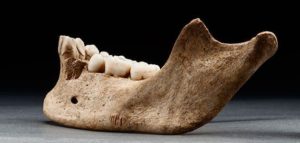

Cut marks on Jane Doe’s jaw bone

British colonists erected a fort on the James River in 1607, making Jamestown the first permanent British settlement in North America.

Jamestown was the logical first step on our quest to understand the nation’s colonial roots. But Liz and I also thought Jamestown would pique the interest of our grandkids–Eva, Abby, and Aydan. Because of research I’d done for my book Tomb Raiders: Real Tales of Grave Robberies, I knew Jamestown’s bones had a grisly story to tell about desperate people trying to survive in a desperate time.

On route to Jamestown, I read “When Bones Speak,” the first chapter of Tomb Raiders. This chapter tells the story of Jane, a teenager who arrived in Jamestown during the Starving Time, and the terrible fate that awaited her in this new world. The grandkids listened, and when we arrived at Jamestown Settlement, they were eager to encounter Jane’s world.

Jane’s reconstructed face

Well, the girls were eager. Poor Aydan had contracted a virus and had a sore throat and was running a low-grade fever. But history waits for no man, or boy. So Liz pumped Aydan with ibuprofen, made sure his face mask was secure, and urged him onward.

Jamestown settlement is a museum and living history site.

The gallery and films showcase the Powhatan Indians, British colonists, and west central Africans, the three distinct cultures who converged upon Virginia in the seventeenth century.

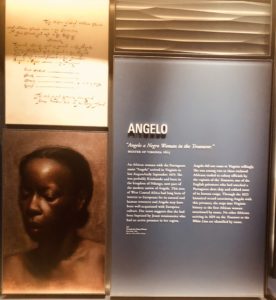

Most exciting to me was the exhibit on the first Africans in North America. When I visited Jamestown about 15 years ago, the story of enslaved Africans was noticeably absent. But since then researchers know much more about how Africans fit into America’s birth story. Historians even know the identity of one captive African woman brought to Jamestown in 1619. Her name was Angela. She was captured from the Ndongo Kingdom in West Africa. Angela survived the transatlantic crossing, attacks by Powhatan Indians, and the hunger and privation that killed so many British colonists. Although little is known about Angela’s life, her name was listed on a colonial muster. This alone distinguishes her from the millions of nameless, faceless enslaved people forcibly brought to America over the centuries.

Angela–an enslaved African brought to Jamestown in 1619

Liz and I could have spent the entire day in the museum, but the grands weren’t having it. We had a brief window of opportunity in which to expose the kiddos to important history before they demanded we head for the nearest swimming hole. So we went outside and found the living history exhibits.

First, we entered Paspahegh Town.

This Indian village has been recreated based on archeological findings and descriptions recorded by 17th century British settlers. The native people who lived here were members of the Powhatan Confederacy, an empire of 30 Algonquin-speaking tribes overseen by Wahunsenacawh, whom the English came to know as Chief Powhatan. The roots of these indigenous people in the Chesapeake region go back some 10,000 years.

Reconstructed Powhatan House

Our kiddos wandered inside reed-covered houses. They listened to reenactors explain how to make fishing nets from plant fibers and how to construct a dug-out canoe. Our grandchildren knew myths about Pocahontas, thank you Walt Disney. But this Indian town, and the rich collection of museum artifacts, gave them a glimpse into the sophisticated culture that existed for thousands of years before Europeans set foot in the Chesapeake.

Making a fish net from plant fiber

Next we followed the footpath to the pier along the James River where three ships loomed—the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery.

These are replicas of the vessels that brought British colonists to Virginia in 1607. It was 90 plus degrees on deck and hot and stuffy as we descended into the bowels of Godspeed.

Aydan was sick, but not so sick he wanted to lay down in a sailor’s berth.

Abby and Eva–Deck hands in training

Later, Eva told me she’d learned three important things about life on a 17th century schooner. “One, you’d get seasick. Two, it would be dirty. And three, it would be stinky.” Stinky indeed.

Can you spot the sailor? What skills were needed for success at this job?

We disembarked and headed up the trail to the palisade that surrounds the recreated 1610 James Fort.

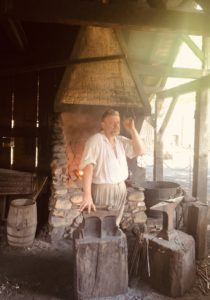

Inside we explored wattle-and-daub buildings with thatch roofs as well as an Anglican church, a court of guard, a storehouse, and the governor’s house.

Striking a pose by the palisade

Blacksmith operating the bellows

There Eva made a sophisticated analysis for a 9-year old. As she compared the houses regular settlers lived in with that of the governor’s house, Eva concluded that “The more important you were, the better life you’d get and the better stuff you’d get.” Yep. That led to a discussion about income inequality today and how sometimes, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

What’s for dinner, Governor?

Just up the road from the Jamestown Settlement is Historic Jamestowne, the original site of the first permanent British settlement in North America.

Now that the kiddos had a mental picture of what life in Jamestown would have looked like in the early 17th century, it was time to show them how archeologists are painstakingly uncovering the past.

The afternoon sun glared down as we crossed a footbridge over a pitch and tar swamp. Poor Aydan trailed behind, his fever rising with the temperature. While Liz took Abby and Aydan to sit in the shade beside the James River, Eva and I talked with archeologists excavating the old fort site.

The past is still being unearthed

For many years, people assumed that erosion had washed all remains of the original Jamestown fort into the river. But in 1996, archeologists found stains of decayed wood where the fort’s palisade had stood. Since then, they have unearthed millions of artifacts, trenches and ditches and timber stains, and graves. These findings reveal a mosaic of life in historic Jamestown and they tell a grisly tale.

In 2012, scientists uncovered a mutilated skull and severed leg bone of a teenage girl. They christened her Jane. Jane’s bones were found among horse and dog bones discarded during the desperate winter of the Starving Time, 1609-1610. Forensic examination of the bones proved that British colonists resorted to cannibalism in a desperate attempt to survive. Primary source documents from the time support this archeological discovery.

The kids found Jane in Historic Jamestown’s archaearium.

This archeology museum showcases some of the two million artifacts that scientists have unearthed on site. Armor, tools, coins, and, yes, bones are all on display. Aydan, Abby, and Eva were somber as they viewed the human remains. Perhaps the thought of how precarious life was for these early settlers gave the kids pause. Or maybe they were just grateful to be in a air-conditioned museum rather than outside in the 90 degree humidity where their Elucidating Grannies kept making them assume historic poses.

The next generation of Jamestown Council members

That night Eva and I discussed how we might have handled the Starving Time.

“Would you have eaten dead bodies in order to survive?” I asked.

My granddaughter paused for a long moment, and then shook her head. “No, because I’d probably vomit all the food I just ate.”

But who can really say how one would react. Desperate times call for desperate measures. And those first colonists were definitely desperate. Jamestown was a hairsbreadth from failure. Out of 300 colonists in the fall of 1609, only 60 were alive in the spring of 1610.

But for the arrival of supply ships and more settlers, the British experiment would have failed.

How would the future of Virginia’s indigenous populations have been different had this occurred? And with no British colony on the Chesapeake, there would have been no point in bringing a shipload of captive Africans there in 1619. Would slavery had taken hold in America?

But these are moot points because Jamestown did survive, at least for a while. A town emerged, becoming the capital of Virginia colony. After the statehouse in Jamestown burned in 1698, the capital moved to Williamsburg. Over time, Jamestown began to disappear. Buildings collapsed. The river eroded the bank, and farmers began to cultivate the land.

However, history did not disappear.

The past just moved underground, waiting for modern archeologists to unearth the stones and bones and reconstruct the tale they had to tell.

Although Jamestown’s role was over, the historic triangle had much more to tell us about colonial America. So the Elucidating Grannies and their history-loving progeny moved on.

Next stop: Colonial Williamsburg

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!