Teaching School Desegregation through the Story of Sylvia Mendez

Picture books are powerful teaching tools, not just for elementary kids but for older readers as well. I have taught, read, and written about American history for decades, but it took a picture book to introduce me to the Mendez family and their fight for school integration.

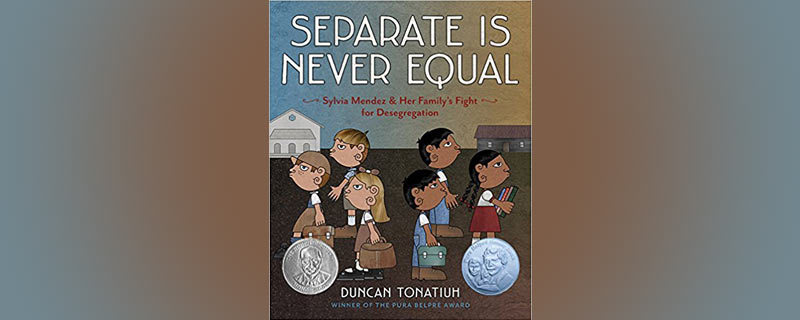

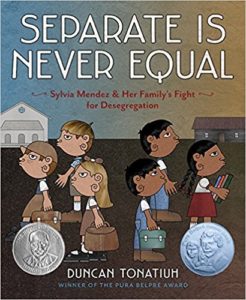

Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation by Duncan Tonatiuh explores a legal case I’d wager is not taught in many history classes. It should be.

Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez moved to Westminster, California with their three children in 1944. Gonzalo was a naturalized U.S. citizen who had been born in Mexico and Felicitas was born in Puerto Rico. Like much of the nation, California was segregated at the time.

Restaurants posted signs to keep Mexicans out.

Public swimming pools were only open to Mexican children on Sundays after which the pools were emptied and filled with clean water.

Schools were segregated too.

In 1898 the United States Supreme Court had ruled in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision that segregated schools were legal as long as they were equal. In California, Mexican children were required to attend so-called “Mexican schools,” facilities that were anything but equal to schools for whites.

Gonzalo Mendez wanted his children to attend the school nearest their house.

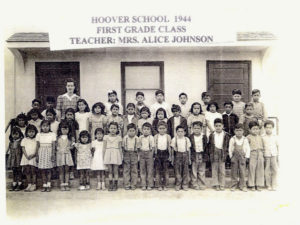

The building was spacious and clean and surrounded by trees. Sylvia especially liked the monkey bars and red swing on the school’s playground. But the principal refused to admit Sylvia and her brothers because this school was only for white children. The Mendezes must attend the Hoover school, a two room shack located in the Mexican neighborhood.

The Hoover school had underpaid teachers, castoff textbooks, and students were taught how to crochet and cook rather than the three R’s. Worse from eight-year-old Sylvia’s perspective, Hoover had no playground.

Although the Mendez children went to Hoover in the fall of 1944, Sylvia’s parents refused to give up the fight for their children’s education. They tried to rally other Mexican families to sign a petition to integrate the schools. But in a community where most Mexicans were migrant workers on farms owned by whites, people were afraid to risk their livelihoods.

Then Gonzalo learned about David Marcus, a lawyer who had helped integrate public swimming pools in San Bernardino. Gonzalo hired Marcus, and the two men convinced four other families to join the legal fight against the schools. Marcus urged the families to do more than just demand better resources for the Mexican schools. He wanted to strike at the heart of segregation itself. The families agreed.

On March 25, 1945, Marcus filed a lawsuit against four school districts in Orange County. This fight would not just be for the Mendez children but for all children of color in California.

Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez

During the five day trial, Sylvia and her little brothers dressed in their best clothes and sat quietly in the courtroom.

Sylvia listened as one of the district superintendents testified why the Mexican children needed to be taught separately from the whites.

The children could not speak English, he claimed.

Sylvia spoke perfect English.

The children were dirty and diseased, he insisted.

Sylvia was clean and healthy.

The children were “inferior” to white children, he argued.

Sylvia might not have known exactly what inferior meant, but she got the message. This white man did not think much of Mexican people.

The next day, Mr. Marcus called one of the plaintiffs, 14-year-old Carol Torres, to the stand. The teenager girl answered every question in perfect English, proving that the superintendent had lied when he claimed the Mexican children only spoke Spanish.

Marcus also called educational specialists who testified about how segregation hurt the children by giving them an “aura of inferiority.” The defense’s argument was persuasive. Judge Paul J. McCormick ruled in favor of the Mexican families.

.

But the fight was not over. The district immediately appealed.

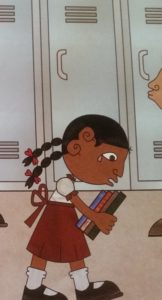

While the case was under appeal, Sylvia was permitted to attend the white elementary school. It is at this point where Duncan Tonatiuh begins his picture book. He sets up a scene that evokes the reader’s sympathy for poor, little Sylvia.

Sylvia had on her black shoes. They were shiny-new. Her hair was perfectly parted in two long trenzas. It was her first day at the Westminster school.

The halls were crowded with students. She was looking for her locker when a young white boy pointed at her and yelled, “Go back to the Mexican school! You don’t belong here!”

Illustration by Duncan Tonatiuh

Sylvia burst into tears. For the rest of the day she did not look at or speak to anyone. That night Sylvia told her mother she did not want to go back to that school. In later interviews Sylvia admits that until that moment she had not really understood what their court challenge was all about. Her mother said, “Don’t you realize that this is what we fought for?” Then it dawned on Sylvia–this fight was about much more than attending a school with a playground.

Sylvia in Grade School

When the Mendez case was tried before the 9th District Court of Appeals, other civil rights groups supported them, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the American Jewish Congress, and the Japanese American Citizens League. Sylvia was surprised that so many people from such different backgrounds were helping her family. Felicitas Mendez said, “When you fight for justice, others will follow.”

On April 15, 1947, the Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s ruling. For the first time in the nation’s history a court had ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional. A few months later, California passed a law integrating public schools across the state.

Seven years later, the United States Supreme Court ruled on a similar case—Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. What the Mendez case did for California, the Brown decision did for the nation. The Supreme Court concluded that segregated schools were “inherently unequal” and must be integrated “with all deliberate speed.”

Because the Brown decision had a national impact, it overshadowed the Mendez case, and few Americans have heard of the Mexican American families who helped establish a legal precedent.

A book like Separate is Never Equal can remedy that. Children need heroes, and Sylvia Mendez and the other Mexican American children who first integrated California’s schools were heroic.

They laid the groundwork for other young people like Linda Brown, Ruby Bridges, and the Little Rock Nine. Felicitas Mendez was right when she said, “When you fight for justice, others will follow.”

TEACHING SUGGESTIONS:

This book could be read aloud to students from second grade to high school. Supplementary activities can extend the learning in different ways depending on the readers’ ages.

Discussion questions for all readers:

- What rights are guaranteed to you as an American citizen? Are there more rights you believe all people should be given? Should a person’s rights be determined by whether someone is a citizen of the United States or not?

- What messages did the school officials communicate to the Mexican families, both directly and indirectly?

- How might these messages affect the way Sylvia and the other Mexican children felt about themselves and their future?

- How would this story be different if all the Mexican families had signed Gonzalo Mendez’ petition?

- How would this story be different if Gonzalo Mendez had been too poor to hire a lawyer?

- What arguments were given throughout the book in favor of segregation and what arguments were given opposing segregation?

Extension Activities:

Primary Grades:

- Read the ending of the book and imagine what will happen next for Sylvia. Write and illustrate three more pages.

- Sylvia was never called to testify in court, but imagine she had been. Write down a series of questions her lawyer, David Marcus, might have asked her and questions the school district’s lawyers might have asked her. If you were in Sylvia’s shoes, how would you answer these questions?

Secondary Grades:

- In 2011 President Obama awarded Sylvia Mendez the Congressional Medal of Freedom. Research Sylvia’s adult life to determine what actions earned her such an honor?

- Research both the Mendez v. Westminster case and the Brown v. Board of Education case. Compare and contrast the two lawsuits.

- Research the state of school integration today in Orange County, California. How racially and ethnically integrated are public schools and what explains the results you find?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!